San Luis Obispo Dairy Industry

A Track Through “Cow Heaven”:

San Luis Obispo Dairying and the Impact of the Railroad

Researched and Written by

Solange Kiehlbauch

December 16, 2016

Before the railroad was established in the sleepy rural county of San Luis Obispo, its inhabitants longed for an efficient means of transportation to connect them to the world. Promotional material produced in the late 1880s reflects this progressive desire, such as a Shakespearean-style verse that read: “We pray thee, therefore, to grant us a means of transportation, that we may dispose of our herds and our olives and the blood of the grape and the orange and the pomegranate.” Although the railroad certainly revolutionized the transport of olives, grapes, and pomegranates as well as the movement of people in San Luis Obispo County, it is its impact on the aforementioned herds – specifically, dairy cows and their products – that is the focus here. This provides a brief history of the dairy industry in San Luis Obispo County, with a particular focus on its origins, influential families and producers, and the impact of the railroad on both local dairying and the country as a whole. Although dairying played a vital role in the transformation and prosperity of San Luis Obispo County, it was the railroad that fulfilled the industry’s potential for expansion and success.

Despite its eventual status as the leading dairy producer in the world, the San Luis Obispo dairy industry emerged from an unlikely origin: a devastating three-year drought. In two consecutive seasons between 1862-63 and 1863-64, a sharp decrease in rainfall left the earth parched and unproductive, rendering formerly lush grazing ground bare and forage utterly exhausted. It was the vast Spanish herds of cattle in particular that suffered, succumbing to starvation at an alarming rate. According to Myron Angel, who penned an extensive history of San Luis Obispo County in 1883, the drought left the region “devastated as if Genghis Khan or Timour the Tartar had passed over it with their hosts, fulfilling their boast that they left no living thing behind nor any verdure in their path.” Despite this devastation, Angel states that the drought was later regarded by the county’s residents as “the blessing of a revolution,” as it served to break up the Spanish ranchos that had previously dominated the region, opening up the land for division among independent farmers and enabling the growth of new industry. Once the rain returned, the primary industry that emerged was dairying. This was largely due to the nature of the land itself. Once proclaimed the “cow country of California,” San Luis Obispo County offered unparalleled grazing land for cattle, as well as a temperate climate that allowed herds to remain outside throughout the year. This climate was also particularly favorable for the production and storage of perishable products such as butter and cheese. The county’s close proximity to the ocean kept forage green for most of the summer, and was supplemented by marshy lands on which the grass continuously renewed itself throughout the year. The sea breeze also served an additional effect, bringing with it “health and vigor to [both] man and beast.” It is no wonder that one of the first dairymen in San Luis Obispo County, E.W. Steele, proclaimed the land to be “cow heaven” when he purchased his first ranch.

In 1866, a successful dairyman from San Mateo named Edgar Willis Steele came to San Luis Obispo County in order to examine the area’s potential for the expansion of his business. Impressed by the “luxuriant” grazing land, he purchased the Corral de Piedra Rancho and established dairies on it. Soon after, he and his brothers George and Isaac Steele purchased additional ranchos and created an expansive dairy network across two separate counties. According to an article from the San Francisco Commercial Herald, by 1870 the Steele Brothers were “the largest owners of milk cows in California.” At this time, their entire herd totaled 1400 head, 750 of which were housed in five separate dairies at Pescadero, San Mateo County, with a similar number in San Luis Obispo County near the town of the same name. Their cows were a superior-milking, easy-keeping cross between American and English breeds, capable of producing 500 to 600 pounds of cheese per head each year. According to Myron Angel, it was the Steele Brothers’ “large capital, experience in business, great enterprise, and unyielding energy” that contributed to their success – and an astounding success it was. In 1882, their cows produced 262, 715 pounds of cheese; a sizable chunk of the county’s annual yield of 1, 567, 350 pounds of butter and 985, 420 pounds of cheese. By 1883 San Luis Obispo was the second highest producer of butter in the state of California (and the first in quality), as well as the first in production of cheese, with the Steele Brothers producing “the largest amount of cheese of any firm in the world.” Besides dairy cows and their associated products, the Steele Brothers also kept and sold beef cattle, sheep, and hogs, as well as crops such as barley and potatoes and a variety of fruit. But it was their butter and cheese that were in highest demand. Their brand was soon known everywhere along the California coast, and even gained international fame in Mexico and China. According to Myron Angel, the Steele Brothers’ success offered definitive proof that “the county was good for other purposes than raising cattle for beef, hides, and tallow.” With the post-drought land appropriation and the subsequent rise of the dairy industry, San Luis Obispo County had officially transformed from its Spanish rancho origins to a distinctly Californian center of agricultural industry.

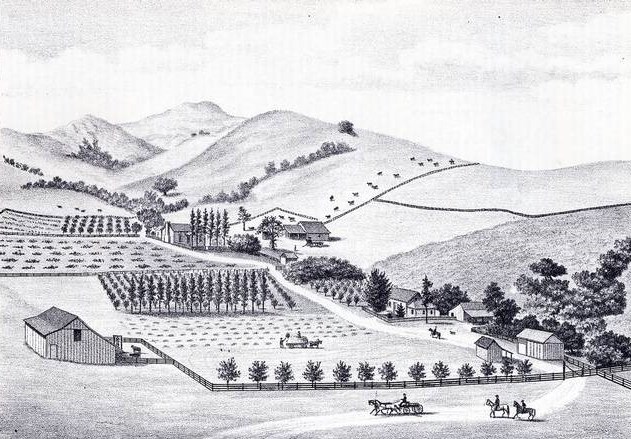

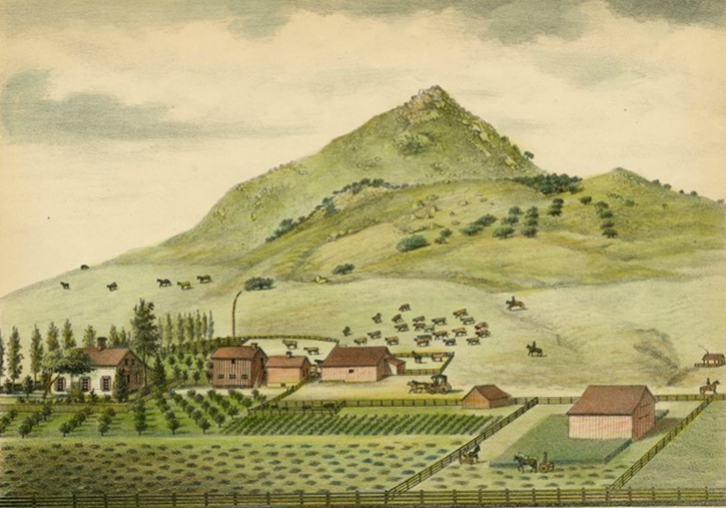

Although the Steele Brothers were arguably the most well-known and influential dairymen in San Luis Obispo County, there were many others who contributed to the development of the county’s lucrative new industry. Alden B. Spooner, for instance, leased 65,000 acres of Pecho y Islay Rancho in 1892, becoming so successful that he was able to buy the land outright ten years later. In the next few years he purchased an additional 9,000 acres of the Pecho Ranch as well as six miles of ocean-front property from Diablo Canyon to Hazard Canyon. His ranch house in Montana De Oro is still in use today as a park ranger headquarters and museum. Spooner raised crops such as barley, wheat, and hay, as well as beef cattle, hogs, horses, and Holstein dairy cows. Although his herds produced an abundant supply of milk, he utilized a clever feat of engineering in order to increase the production of butter. By damming a narrow gorge in Islay Creek and running water though a system of troughs, trenches, and a homemade water wheel, he was able to apply power to the separator and churn inside the milk house – a highly efficient and self-sufficient system of production. Another influential dairyman was Patrick O’Connor, who came to California in 1861 to seek his fortune in the mines. In 1866, he switched trades and came to work at one of the Steele Brothers’ dairies. After the expiration of his lease, he had gathered enough knowledge to establish his own dairy on a part of the Los Osos Rancho. A lithograph of O’Connor’s ranch depicts the typical arrangement of a San Luis Obispo dairy, with free-range cattle grazing on the lush hills that characterize the county (Figure 1). On this 1,191-acre property he kept 140 head of well-bred cattle, which produced 335 pounds of cheese a day. According to Myron Angel, the superior quality of his product led to O’Connor’s reputation as “the premier cheese-maker of San Luis Obispo County.”

The prosperity and rapid growth of the San Luis Obispo dairy industry also led to the development of large-scale production companies. In 1871, Thomas Bowen and John C. Baker purchased a three-acre parcel east of the present town of Harmony and constructed what would become the Excelsior Cheese Factory. This establishment, which was the first of its kind in the county and one of the first in the state, set a ” ‘prototype’ of industrial cheese-making operations” in San Luis Obispo. Although this institution was only moderately successful, and very little is known about the factory itself, it helped to establish a “local, factory-based economy that persisted until the mid twentieth century.” Thus, the Excelsior Cheese factory’s most important contribution was the precedent it set for the development of commercial cheese-making in the Harmony Valley. The prosperity and rapid growth of the San Luis Obispo dairy industry had attracted sizable amounts of Swiss-Italian immigrants, who came to work on established farms as milkers before purchasing their own farms. One of these industrious men was M.G. Salmina, who had settled in Cambria with his brother in 1891. After working in the dairy industry and completing a course on creamery manufacturing at U.C. Berkeley, Salmina established the Diamond Creamery in order to improve the poor market reputation of San Luis Obispo County butter. By offering a premium for fresh, sweet cream, he succeeded in this mission, but soon set his sights on a more ambitious goal: the establishment of a creamery cooperative. In September 1913, this vision became a reality, as a group of Swiss-Italian dairymen signed the first cooperative marketing agreement, thus establishing the Harmony Valley Creamery Association. Soon after, the Association experienced two watershed events between 1919-1920: membership into the Challenge Creamery and Butter Association, and an upgraded facility. After moving to San Luis Obispo in 1930, the creamery served as an important hub for the county’s dairy processing. As such, the Harmony Valley Creamery Association formed an “integral part in the economic vitality of the central coast region,” continuing production until the early 1960s.

Although San Luis Obispo County had transformed itself from a drought-stricken wasteland to a prosperous agricultural supplier due in large part to its dairy industry, there was also another, often overlooked factor that played an essential role in this success. Despite its rich grazing land, fertile soil, and temperate climate, the county faced a significant drawback: isolation. A lack of harbors and rough, underdeveloped roads led to a stifling feeling of seclusion among its populace. This problem was especially troublesome from an economic standpoint, as demand for products from San Luis Obispo farms increased both north in San Francisco and south in Los Angeles with no efficient means of transportation. Thus, the agricultural possibilities of both San Luis Obispo and Santa Barbara counties were “significantly impeded by the absence of an economical way to export the products of a developing region.” Myron Angel also echoed this frustration, stating that without an efficient means of transportation, “to carry on farming, or fruit culture, or dairying, or any other of the ordinary classes of agriculture was a difficult problem.” A glimmer of hope arrived in 1876 with the construction of a local narrow gauge railroad, the Pacific Coast railway. This line somewhat improved the county’s export situation, increasing the marketability of its agricultural products and fueling the development of additional farmland for crops such as wheat, barley, and beans as well as the area’s “prized” dairy products . Its small scale of operation and limited service area, however, reduced the full scope of its impact. That all changed with the arrival of the Southern Pacific Railroad, which steamed into San Luis Obispo on May 5, 1894, to an uproarious three-day celebration. Finally, its residents thought, “the era of the railroad had arrived” – and indeed it had. In addition to attracting settlers, who were seduced by promotional materials such as Sunset magazine that celebrated the “California land and lifestyle,” the railroad revolutionized the transport of agricultural goods, including the county’s world-renowned dairy products.

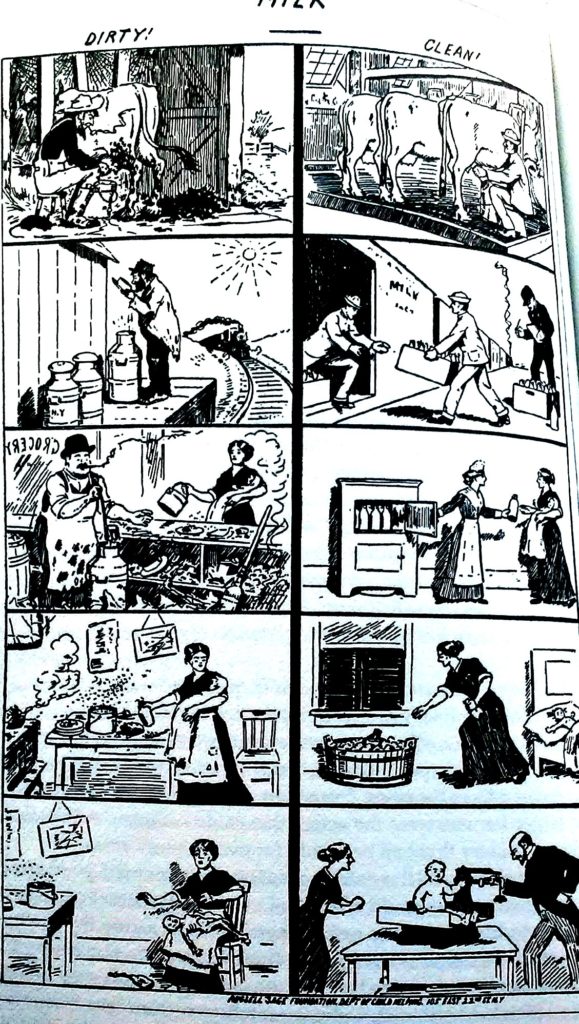

The revolutionary impact of the railroad upon dairy export was not limited to San Luis Obispo County; it was, in fact, a countrywide phenomenon. In her book Nature’s Perfect Food: How Milk Became America’s Drink, sociologist and professor E. Melanie Du Puis discusses the growth of America’s dairy industry, with a particular focus on industrial processes that facilitated its expansion. According to Du Puis, milk used to be a dangerous food. Its consumption was a rare luxury, reserved mainly for infants and children, although all too often with fatal effects. This was largely the result of problems with its exportation. As more people moved to the cities, milk had to be transported from local dairies, which posed a particular hazard for such a delicate commodity. Thus, as Du Puis informs us, “the time it took and the number of hands milk passed through from the farm to the consumer led to both a deterioration and adulteration of the product.” In her examination of the transformation of rural life in 19th century America, Sally McMurry argues that it was a combination of improved sanitation, refrigeration, urbanization, and efficient rail transport that made American dairy products safer and more widespread. An educational placard from 1911, for example, depicts the transportation of milk by rail, with an emphasis on the cleanliness and efficiency of this method (Figure 2). By the 1850s, major American cities received a significant portion of their dairy products by rail; New York City, for instance, acquired a third of its milk supply this way. As a result of this phenomenon, in the half century after 1830, the supply of milk cows steadily rose, and dairy production of all types increased by 300%. By the 1880s the renowned American dairyman H.E. Alvod declared that dairying had become “the greatest single agricultural interest in America.”

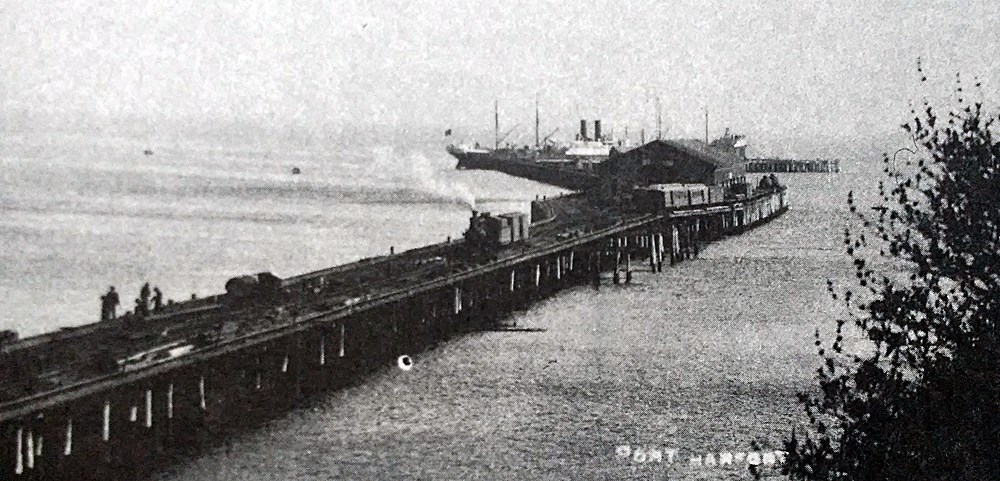

Although scholars such as Du Puis and McMurry have focused their analysis of the impact of the railroad on the dairy industry in the northern states of America, the county of San Luis Obispo experienced a similar version of this phenomenon. Prior to the advent of the county’s prolific dairy industry, cities such as San Francisco had received products such as butter and cheese by ship from Boston, New York, and Chile. Unfortunately, these supplies, which were low-grade to begin with, were often spoiled and inedible as a result of their long voyages. Despite this flawed system, there was no other alternative, as local dairy production was meager and largely dependent on milk from Mexican beef cattle. But as San Luis Obispo’s dairy industry bloomed, a viable alternative emerged, and the county’s products were soon in high demand both locally and in cities such as San Francisco and Los Angeles. With this increased demand came the need for a more efficient means of transportation to bring such products to market. Both steamships and the railroad – often in conjunction with each other, as shown in Figure 3 – would effectively serve this purpose, allowing the county’s excess dairy products to reach these markets while maintaining their superior quality. Recognizing the railroad’s potential to expand their business, San Luis Obispo dairy producers were soon clamoring for its construction. The Los Osos Valley dairyman Horatio Moore Warden, for instance, funded many improvements for the county, including a $1500 donation towards the building of the railroad. As a result, the dairy boom facilitated the building of wharfs, lighthouses, and railroads to transport San Luis Obispo County’s exceptional butter and cheese.

Numerous sources from the county’s local history archives attest to the importance of the railroad on the dairy industry as well as specific details of its operation. For example, an article in The Pacific Dairy Review from April 1, 1920 discusses a favorable dairy season and the large supply of butter exported by railcar to San Francisco. Another publication from 1924 states that the neighboring central coast county of San Joaquin shipped an average of 50,000 pounds of cream a month by train. Although the Pacific Coast railway used ventilated boxcars rather than true refrigerated cars to transport perishable goods such as butter and eggs, San Luis Obispo County did eventually use refrigerated cars to transport various agricultural products. In addition, ice and cold storage were utilized in cities such as San Francisco for perishable goods brought in from the county. An ad from 1920, for instance, boasts of cold storage for butter, eggs, and cheese “in direct connection with the railroad.” Cows themselves were also shipped by rail, as an informational pamphlet from Hoard’s Dairy attests. According to this document, a “silly” notion had developed that rides along the coastal lines would improve the quality of a dairy sire – an idea which seems to echo Myron Angel’s observation of the sea breeze bringing “health and vigor to man and beast.” With this efficient means of transport, technological innovation, and increased production yield, San Luis Obispo dairymen recognized the importance of the railroad to their business. Understanding the advantages from close proximity to the tracks, some dairymen even relocated their farms in order to increase their shipments. The Spooner family, for example, bought a ranch and moved their creamery to the Edna Valley around 1920 in order to facilitate shipping their dairy products by rail. The railroad also enabled the development of a new kind of cheese, when Monterey County businessman David Jacks used local milk to create a soft, white cheese that bore his name: Monterey Jack. This product, which made its first appearance by railcar to San Francisco in 1882, became what many experts consider “the most importance cheese created in the U.S.” Taken together, this combination of industry, innovation, and efficient transportation allowed dairying to play a vital role in the creation of “industries and infrastructure for the future of San Luis Obispo County.”

The San Luis Obispo dairy industry emerged from its unlikely origins in a drought-stricken wasteland to become a world-renowned producer of the finest cheese and butter. The region’s natural attributes and temperate climate set the stage for this transformation, but it was the county’s industrious and enterprising dairymen that brought San Luis Obispo to vibrant life. Influential figures such as E.W. Steele laid the foundations for a successful business model, and enterprises such as the Harmony Valley Creamery consolidated the county’s rich variety of resources. Despite the early success of this newly developed industry, the region’s isolation posed a substantial problem for the marketing of its ever-increasing surplus products. With the construction of the railroad, San Luis Obispo’s dairy and agricultural industry became effectively revolutionized, mirroring a trend that also occurred in other parts of the country. Numerous sources attest to the transformative power of the railroad on San Luis Obispo dairying. As such, the combination of a naturally conducive landscape, enterprising individuals, and technological advances set the stage for San Luis Obispo County’s prosperity and success.

Bibliography

Angel, Myron. “Agriculture Continued.” In History of San Luis Obispo County, California, 222-233. Centennial Edition Facsimile Reproduction. San Miguel: Friends of the Adobes, 1983.

Carr, Paula Juelke. “Harmony Along the Coast.” In Road Scholars: Transportation Histories of the Central California Coast, edited by Thomas Wheeler, 28-32. San Luis Obispo: Heritage Shared, 2008.

DuPuis, E. Melanie. Nature’s Perfect Food: How Milk Became America’s Drink. New York: New York University Press, 2002.

McMurry, Sally. Transforming Rural Life: Dairying Families and Agricultural Change, 1820-1885. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995.

Nicholson, Loren. Rails Across the Ranchos. San Luis Obispo: California Heritage Publishing Associates, 1993.

“Our Area.” Central Coast Creamery. Accessed December 16, 2016. http://www.centralcoastcreamery.com/our-area/.

Pavlik, Robert. “A Railroad Runs Through It: The San Luis Obispo Southern Pacific Railroad Historic District.” In Road Scholars: Transportation Histories of the Central California Coast, edited by Thomas Wheeler, 4-15. San Luis Obispo: Heritage Shared, 2008.

“Railroad Rides and Salt Air.” In Better Dairy Herds Through Breeding. Fort Atkinson: W.D. Hoards and Sons, 1934.

Sullivan, Joan. “Dairying in Los Osos Valley.” 6th ed. In Los Osos Valley, 55-62. Los Osos: The Bay News, 2008.

“Two Centuries of Prominence and Personalities.” California Milk Advisory Board. Last modified June 2009. Accessed December 16, 2016. http://www.californiadairypressroom.com/Press_Kit/History_of_Dairy_ndustry.

Wescott, Kenneth E. and Curtiss H. Johnson. The Pacific Coast Railway. Los Altos: Benchmark Publications, 1998.

Yenne, Bill. The History of the Southern Pacific. New York: Bison Books, 1985.